Do internet and mobile-based therapies for self-injurious thoughts and behaviour help?

Peter Taylor

Internet and mobile technology is changing the way we think about healthcare and intervention. This is the case not just for physical but also mental health. Psychological therapies for prevalent mental health difficulties including depression and anxiety can be delivered via internet websites and through mobile-phone applications (referred to as eHealth and mHealth, respectively) and evidence suggests such approach can be beneficial. Recently, there has also been increasing interest in using eHealth and mHealth interventions to help prevent self-injurious thoughts and behaviour. I use the term self-injurious thoughts and behaviour to refer broadly to a spectrum of behaviours including suicidal thinking, attempts and non-suicidal self-injury. Whilst eHealth and mHealth interventions for self-injurious thoughts and behaviour vary widely, many involve the delivery of psycho-education and coping skills or strategies, based on established therapies like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), through a phone app or internet webpage. Support in seeking help or contact others in a crisis is also a common feature. Other more novel approaches that have been developed include the use of a behavioural conditioning task, delivered through a phone app, designed to reduce self-injurious behaviour, and an internet-delivered reflective writing task designed to boost self-esteem.

Internet and mobile technology is changing the way we think about healthcare and intervention.

The potential benefits of eHealth and mHealth interventions for self-injurious thoughts and behaviour are clear. Many traditional barriers to access, including the difficulty getting to appointments, the availability of therapists, the stigma that can make attending a face-to-face appointment incredibly difficult. Moreover, for eHealth and mHealth interventions that are designed to work alongside face-to-face therapeutic approaches, there is the potential to extend the work and support outside of the therapy room and into clients’ everyday life. These potential benefits become more important when we think about the challenges to accessing support present in many lower and middle income countries (LAMIC). In such contexts, the difficulties in travelling to clinics or services, and the availability of trained clinicians, becomes a larger problem. This is particularly relevant when considering self-injurious thoughts and behaviour, as the World Health Organisation have estimated that 78% of annual suicides occur in LAMICs. The problem posed by suicide and self-injurious thoughts and behaviour in countries like India and Pakistan is now recognised by international research efforts that aim to improve monitoring and understanding. eHealth and mHealth therefore may make a valuable contribution to self-injurious behaviour prevention in these settings, and more widely.

Caution is needed, however. It is important to ascertain that eHealth and mHealth interventions for self-injurious thoughts and behaviour can actually help people. This is not just a question of clinical efficacy (i.e. do they lead to reductions in the risk of self-injurious thoughts and behaviour) but also acceptability to clients and feasibility. Do the clients using these interventions feel they are of value, and do they engage and stick with such interventions? There is evidence that the relationship that develops between a client and therapist is an important factor in informing the outcome of the therapy. For many therapeutic approaches, this relationship is viewed as a key driver of change. For eHealth and mHealth interventions this relationship may be absent (where there is no human therapist involved) or more remote (where a human therapist connects with clients through the app or website), and this may have implications for the acceptability as well as the effectiveness of these interventions.

Given these considerations outlined above, we recently conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials focused on eHealth and mHealth interventions that are specifically aimed at preventing self-injurious thoughts and behaviour. We identified 22 eligible trials. One immediately apparent difficulty with the evidence base so far is the reliance on single-arm trials (i.e. lacking a control group), and often very small samples. The lack of control groups in particular means that it is difficult to attribute any changes to the interventions themselves. Consequently, whilst there is preliminary evidence that these interventions are associated with reductions in self-injurious behaviour, caution is needed in interpreting these findings.

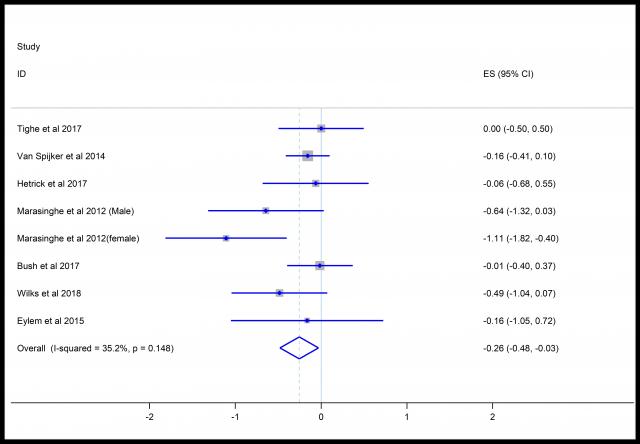

Our meta-analyses of these data focused specifically on suicidal thinking or ideation, this being the most prevalent outcome across trials. A meta-analysis of the treatment effects, at the end of treatment, from across 11 randomized controlled trials suggested a small positive treatment effect, which was not statistically significant. This meta-analysis included a variety of different types of intervention and different samples though, which will have contributed to the inconsistency in treatment effects between studies. In other ways, the treatment effect varied between trials and this variation may reflect meaningful differences between the trials. The type of control or comparator was one characteristic that varied between trials. When we conducted a meta-analysis just on those trials that compared the intervention to “treatment as usual” (i.e. what the standard treatment would be people within that health care system), a slightly larger, significant treatment effect was found (see Figure 1).

We also looked at the data regarding participants’ experience of using the intervention, and whether they stuck with the intervention or not. On the whole these results were positive. Participants tended to use the interventions and to report they were helpful. A number of trials suggested a trend, however, whereby over time participants became less likely to continue to use the intervention. This information is important when we consider the feasibility and acceptability of these interventions.

There remain some important gaps in this evidence base. Additional, larger, controlled-trials would be beneficial, especially those designed to see if the intervention could help reduce self-injurious behaviour. Also, of the 22 trials we looked at, only one took place in a LAMIC, namely Sri Lanka, and so it remains unclear how useful such interventions might be in these contexts.

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Forest plot outlining the effects of intervention on suicidal ideation when compared to treatment as usual. The x-axis represents the size of the effect (Hedges g) with a negative value suggesting a beneficial effect of treatment. The diamond at the bottom of the graph represents the pooled overall effect. The results are from a random-effects meta-analysis.

In summary, eHealth and mHealth interventions for self-injurious thoughts and behaviour show promise as a way of further supporting and helping individuals struggling with these experiences. However, important gaps remain in the evidence, and currently caution is needed in recommending such interventions to clients and patients.

The review paper is recently published as:

Arshad, U., Ul-Ain, F., Gauntlett, J., Husain, N., Chaudhry, N., & Taylor, P. J. (2019). A systematic review of the evidence supporting mobile and internet-based psychological interventions for self-harm. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior.

Publication date: 11 June 2019